“Research is a process of steps used to collect and analyze information to increase our understanding of a topic or issue”. It consists of three steps: pose a question, collect data to answer the question, and present an answer to the question. –John W. Creswell

Willison & O’Regan present a broader definition of student research as “a continuum of knowledge production, from knowledge new to the learner to knowledge new to humankind, moving from the commonly known, to the commonly not known, to the totally unknown.” Based on this interpretation of research they specify six facts of the research process and devised a research skill development framework, drawing together facets of research with degrees of student autonomy (Willison & O’Regan, 2007):

Research with different levels of student autonomy

Prescribed Research: Highly structured directions and modelling from educator prompt researching

Bounded Research: Boundaries set by and limited directions from educator channel researching

Scaffolded Research: Scaffolds placed by educator shape independent researching

Open-ended Research: Students initiate research and this is guided by the educator.

Unbounded Research: Students determine guidelines for researching that are in accord with discipline or context

Position Research in Your Course

Students connect with research and researchers by (Fung, 2017):

finding out about research

Exploring what research, within and/or is across disciplines

Investigating different research methodologies and associated methods

Reading, seeing or hearing about current research studies, both the approaches being undertaken and the emergent findings

Observing research being undertaken in real time (face-to-face or online)

talking about research

Meeting individual researchers and engaging in dialogue with them

Discussing others’ research informally through discussion (face-to-face or online)

Undertaking specific peer review activities

Participating in events such as seminars and conferences.

doing research

Engaging in collaborative enquiry as part of a peer group

Undertaking individual enquiry

Undertaking a research project (as part of a team, and individually)

Evaluating one’s own research, including ethical considerations

producing research outputs

Developing awareness of ways in which research is already communicated to others

Communicating the findings of own research effectively to different audiences

Engaging with different kinds of audience (including alumni), face-to-face or online, to develop ideas in partnership

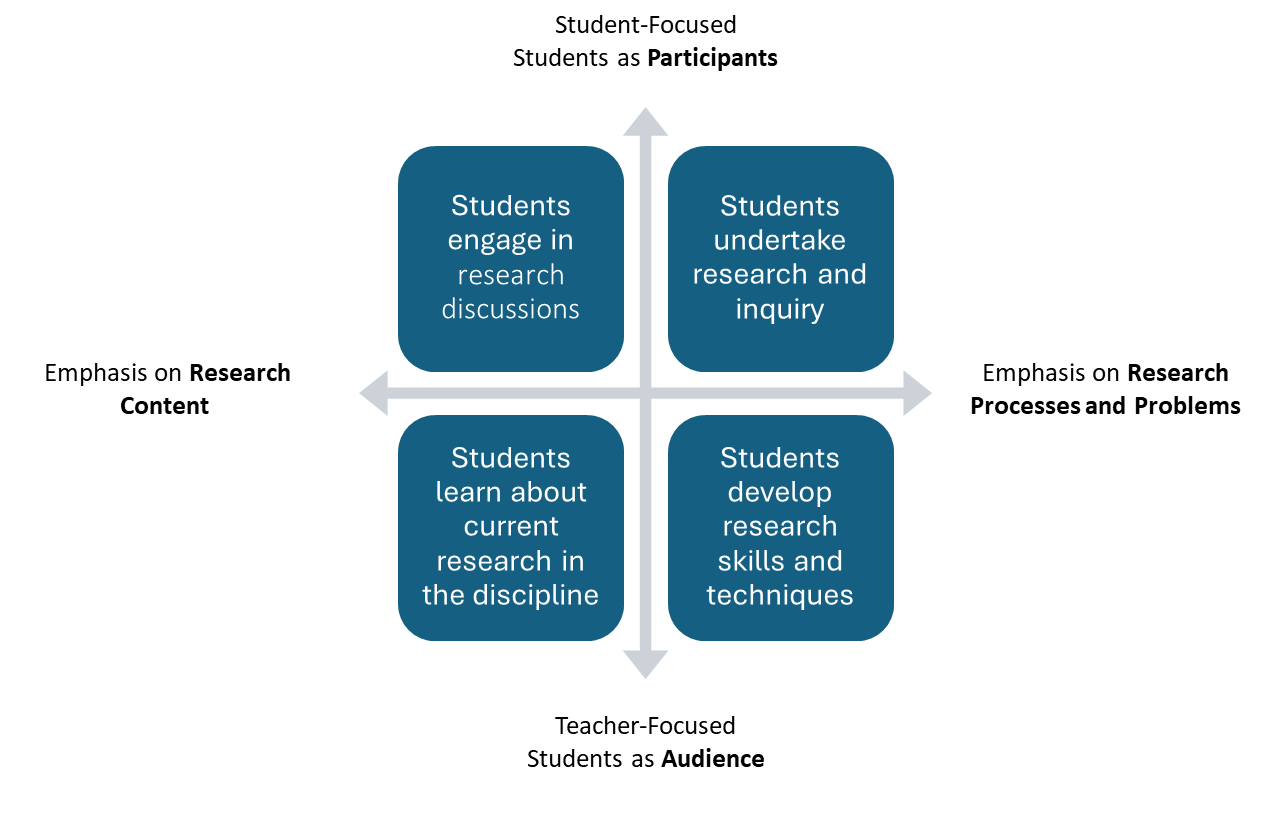

There are a number of models or approaches to the positioning of research within the curriculum. These include the ones in the image below, adapted from (Healey, 2005)

How to Integrate Research into a Course

Research-based learning can be embedded in any course by aligning activities with students’ developmental stages and disciplinary norms.

Here are some highlights from our CTL teaching and learning at lunch discussions:

Attitudes/Mindset Needed for Research

curiosity

perseverance

risk-taking

global citizenship

responsiveness to change

responsibility

Common Challenges for Students

evaluating research questions and estimating time and resources associated with a given question;

discipline-based academic reading and writing;

choosing an appropriate methodology that aligns with a research question;

managing a project, etc.

Expectations and practices in different level courses:

100-level: basics fundamental understanding, train students on research methods

200-level: disseminating the information; read papers and demonstrate their understanding & come up with follow-up research questions

300-level: identify research gaps; come up with a good question and the research plan; independent research to execute the plan

Grad EAP: develop qualitative skills for future research experience

Below are strategies for incorporating research in realistic and meaningful ways, based on both pedagogical research and DKU faculty experiences.

Scaffold Research Skills

Rather than assigning a full project all at once, break research into manageable skill-building steps across the semester:

Find and evaluate sources: Teach students how to distinguish peer-reviewed articles from popular sources.

Understand paper structure: Use Perusall or guided reading questions to walk students through academic papers—especially methods and results.

Interpret data: Use simulated or real data sets; create repeated opportunities to analyze and present findings.

Formulate questions: Use journals or mini-proposals where students develop and revise research questions over time.

Design Research-Infused Assignments

100-Level Courses

Focus on foundational research literacy: be realistic about the student competency and help students learn how to read and understand academic papers without being overwhelmed.

Example from Biology: Students read selected research papers using Perusall and are guided to focus on the methodology sections to inform their lab report writing.

Example from EAP: Introduce research paper structures and help students recognize genre conventions. Assign short writing tasks on data interpretation and crafting thesis statements supported by quantifiable evidence;

Example from Social Sciences: Use simulated data for hands-on activities. Incorporate tutorial videos and step-by-step prompts to support learning.

Example from Material Science: Assign students to read recent papers and extract relevant information that aligns with their personal or academic interests. Practice summarizing and presenting the content.

200-Level Courses

Emphasize method application and analytical reasoning.

Students should read academic texts, demonstrate comprehension, and generate follow-up questions that could lead to research projects.

Example from Biology: Lab courses can include linking experiments to research literature.

Example from Social Sciences: Repeat exercises to help students practice interpreting and analyzing data more independently.

Online tools, recorded workshops, or curated resources can support the increasing complexity of tasks.

300-Level Courses

Encourage independent research design and execution.

Students identify gaps in the literature, formulate research questions, and draft research plans.

Support can include peer feedback, targeted workshops, and mentoring sessions to guide the research process.

Graduate EAP

Focus on qualitative and critical thinking skills to prepare for disciplinary research.

Activities may include designing interviews, practicing coding qualitative data, or conducting literature synthesis with a focus on conceptual frameworks.

Create Authentic Audiences

When students present to real or semi-real audiences, their motivation and engagement often increase.

Presentations at class symposia or student research days

Contributions to course blogs, zines, or open-source platforms

Group projects where findings are shared with other sections, stakeholders, or peer groups

Support Through Resources and Community

Online resources: Provide curated readings, databases, and video tutorials.

Workshops: Collaborate with librarians, the writing and language studio, or the research office.

Mentorship: Encourage informal mentoring from faculty or advanced students to help guide inquiry and build confidence.

Recommendations on Assessing Research Projects

Most students are new to research, so assessment should nurture and guide rather than penalize. Overly rigid criteria and emphasis on the end product alone can discourage creativity and risk-taking. By valuing the research process—questioning, exploration, and reflection—faculty can help students build confidence and engage deeply with inquiry. Here are some recommendations when you design your assessments:

1. Align Assessment with Learning Goals: Clearly define what aspect of research you’re assessing: Is it research skills (e.g., formulating a question), critical thinking, written communication, or domain knowledge? Expectations should vary depending on course levels. Use backward design and start from your research-related learning outcomes and design tasks and rubrics that support them.

2. Assess Both Process and Product

Assess research process elements, such as:

Formulating and refining research questions

Searching and evaluating sources

Designing a method or framework

Data collection, interpretation, and ethical handling

Iterative thinking and problem-solving

Assess final products, such as:

Research papers, reports, presentations, posters

Creative outputs or portfolios

Reflection papers or process memos explaining decisions

3. Use Transparent, Criteria-Based Rubrics: See our guide on Rubrics.

4. Include Reflection and Metacognition

Have students submit research journals, annotated bibliographies, learning reflections to track their development.

Include prompts like:

“What would you do differently next time?”

“What challenges did you face and how did you resolve them?”

5. Consider Formative and Peer Assessment

Break the project into milestones and provide low-stakes feedback along the way.

Use peer review for drafts, proposals, or presentations to support revision and foster a research community.

More DKU examples

- Prof. Floyd Beckford shares his experience implementing CUREs (course-based undergraduate research experiences): Exploring CUREs in DKU Courses – Diving into the Unknown Together – Duke Learning Innovation

- Prof. Daniel Weissglass shares his research-led teaching approach: https://lile.duke.edu/blog/2024/09/student-centered-learning/

References

Healey, M. (2005). Linking research and teaching: Exploring disciplinary spaces and the role of inquiry-based learning. Reshaping the University.

Fung, D. (2017). A Connected Curriculum for Higher Education. UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781911576358

Willison, J., & O’Regan, K. (2007). Commonly known, commonly not known, totally unknown: A framework for students becoming researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 26, 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658609

Additional Resources

Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2009). Developing undergraduate research and inquiry. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-undergraduate-research-and-inquiry

Walkington, H. (2015). Students as researchers: Supporting undergraduate research in the disciplines in higher education. The higher education academy, 1, 1-34.