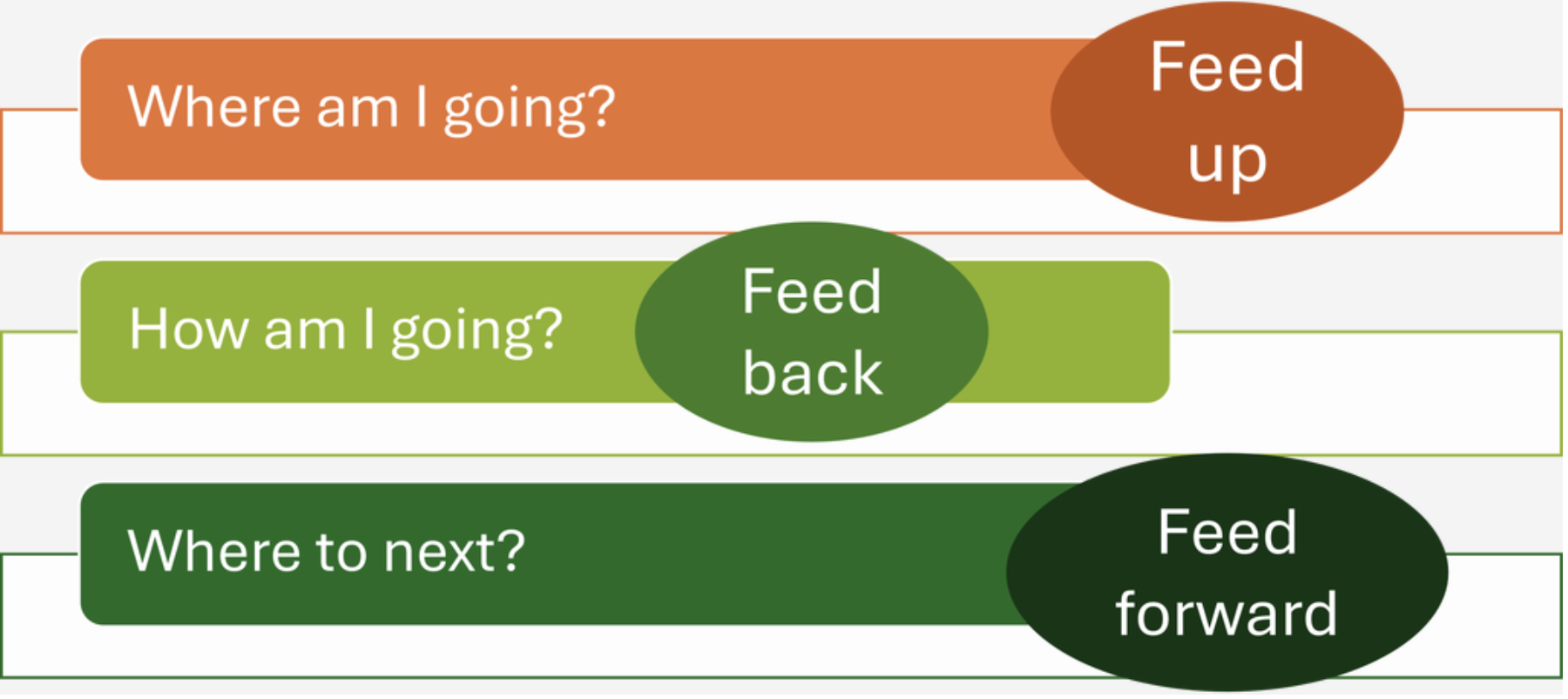

Seeking, making sense of, and using feedback is an essential part of learning. Effective feedback for learning is timely, specific, and encourages reflection and growth. Hattie & Timperley (2007) proposed the Three Feedback Questions to which both teachers and students should seek answers:

Where am I going? (Feed Up)

How am I going? (Feed Back)

Where to next? (Feed Forward)

Feed Up clarifies the learning goals and success criteria, helping students see the purpose and direction of their work. Feed Back provides information on what students have done well and where they need improvement, based on current performance. Feed Forward offers specific guidance on what steps to take next to improve and progress toward the goals. Together, these three types of feedback form a continuous cycle that drives meaningful learning. (Hattie & Timperley, 2007)

Focus of Feedback

Feedback about the … | Description | Example |

Task/product | How well tasks are understood and performed, also known as corrective feedback | Telling a student when an answer is correct or incorrect or asking the student to provide more of or different information. |

Process | More directly aimed at the processing of information, or learning processes requiring understanding or completing the task | “You’re asked to compare these ideas. For example, you could try to see how they are similar, how they are different… How do they relate together?” |

Self-regulation | It is more focused on helping the student to monitor his or her own learning process and is usually in the form of probing or reflective questions. | “You checked your answer with the resource book [self-help] and found that you got it wrong. Do you have any idea why you got it wrong? What strategy did you use? Can you think of another strategy to try?” |

The Learner as a Person | Personal evaluations and affect (usually positive) about the learner | “You are a great student” “That’s an intelligent response, well done.” |

Effective feedback operates at multiple levels—task, process, and self-regulation—and is most powerful when it helps students identify and revise misconceptions, develop better strategies, and stay engaged with learning. Feedback should guide learners from understanding a task to developing strategies and regulating their own learning. As students gain mastery, this leads to increased confidence and motivation. In contrast, feedback focused on the learner as a person (like praise) is typically ineffective, as it does not address learning goals and can discourage students from taking risks or exerting effort. (Hattie & Timperley, 2007)

Strategies of giving effective feedback

Focus on learning instead of evaluation: Frame feedback as part of learning, not just a grade justification. Emphasize progress and growth over perfection. Encourage a growth mindset by highlighting effort, strategy, and improvement.

Create a culture of feedback and involve students in the feedback process: Help students appreciate the value of (both giving and receiving) feedback and understand their active role in the feedback process. Provide students opportunities to seek feedback from various sources and use feedback to improve their work. Use peer review or self-assessment to develop students’ evaluative judgment.

One example to involve students in feedback: Professor Joe Davies provides a coversheet for students to list aspects of their assignments that they would like to receive feedback as well as the areas that they do not need feedback.

Encourage Dialogue and close the Feedback Loop. Make using feedback an explicit part of the learning process. Give time for revision, reflection, or response. Consider requiring a short “feedback reflection” assignment before resubmission.

Be timely: Quick check-ins or brief notes can be more impactful than delayed, detailed critiques. In the fast-paced 7-week system at DKU, it is even more important to consider the timing of your feedback. Take advantages of technologies to make your feedback process more efficient.

Be specific and give actionable advice: Positive feedback to assure students they are on the right track toward the learning goals may motivate students but empty praises like “good job” are not effective without telling students what they are doing right.

Align your feedback with the learning objectives: Refer to the learning objective of the assignment as well as course level objectives. Focus on 2–3 key areas for improvement rather than correcting everything.

Use a variety of modes of delivery: Mix written, audio, video, and in-person feedback when appropriate. Audio or video feedback can feel more personal and engaging. Use in-class activities for instant group feedback (e.g., anonymous polls, think-pair-share).

Student Feedback Literacy

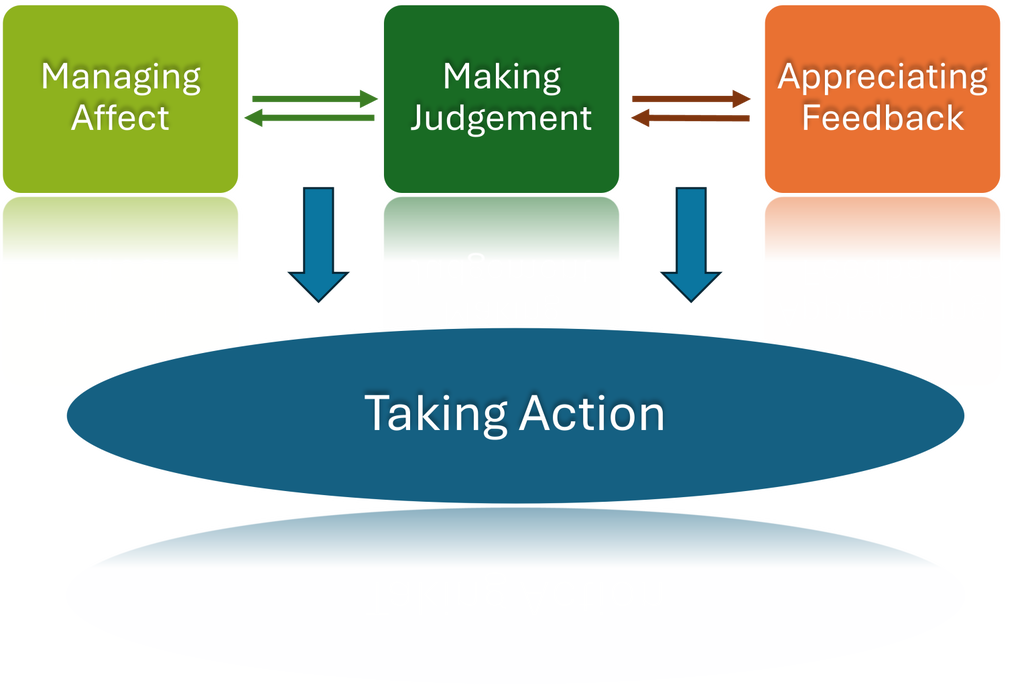

To benefit from feedback, students need more than access to comments — they need feedback literacy: the ability to understand, process, and act on feedback for improvement. Carless and Boud (2018) outline four key dimensions of student feedback literacy:

Appreciating Feedback

Developing a mindset that values feedback as an opportunity for learning, rather than as judgment.Making Judgments

Cultivating the ability to evaluate the quality of work — both others’ and one’s own — through comparison with standards and exemplars.Managing Affect

Navigating the emotional impact of feedback, including building resilience and openness to critique.Taking Action

Using feedback to plan and make changes in future work — turning input into improvement.

When instructors design activities that foster these dimensions — such as peer review, guided self-assessment, and feedback dialogues — they help students become active agents in their learning, not just passive recipients of comments.

DKU Resources

- Professor Joe Davies’ works on feedback sponsored by the CTL teaching grant: Feedback Literacy Workshop_March 2025 | Powered by Box

- Gradescope Guide

- How do I use Speedgrader?

References:

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487 (Original work published 2007)

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354